This post was originally published by the Hoosier State Chronicles Blog, a project of the Indiana State Library.

By Brock Stafford

The American fight for women’s suffrage pre-dated the Civil War by over a decade, yet the struggle continued well into the 20th century. Both national and local suffrage groups utilized varying strategies to push for women’s right to vote, and it was the combination of tactics at both the national and state level that finally achieved universal suffrage through the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. By this time, however, early leaders in the Suffrage Movement of the United States had passed, such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and a new generation of leaders had taken up the torch.

In Indiana, several women pursued careers in journalism as a way to promote their cause, and their contributions are still visible in the newspapers of Hoosier State Chronicles. Three of these women, Ida Husted Harper, Mary Hannah Krout, and Esther Griffin White, represent Hoosier journalists with prestigious careers in education, non-fiction writing, and politics. Their articles and columns for newspapers like Terre Haute’s Saturday Evening Mail and Gazette, The Crawfordsville Journal, and the Richmond Palladium paint a picture of women moving beyond writing under pseudonyms while delving into issues of voting, cultural expectations, social norms, and the world outside of Indiana.

Ida Husted Harper

The earliest of the three women, Ida Husted Harper, would be considered fairly conservative by modern viewers in her approach to suffrage, but her influence on the movement was certainly the most pronounced. A friend and frequent collaborator with Susan B. Anthony, Harper may be best known for her role as historian of the Suffrage Movement and biographer of Anthony, but her newspaper career in Terre Haute and other cities throughout the country was equally notable.

Born Ida Husted, she spent her part of her childhood in Franklin County, eventually moving to and attending high school in Muncie. She briefly attended Indiana University before taking a position as principal and educator in the City of Peru. She married Thomas Harper in 1871, and relocated for his career in law to Terre Haute, effectively ending her career in education. This change ended up being fortuitous, as her new social connections in Terre Haute brought her into communications with notable Hoosier politician and Terre Haute native, Eugene V. Debs. According to Indiana 200, Debs served in politics at the same time as Ida’s husband, Thomas. Debs was also heavily involved in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, (a civic organization advocating for improvements in the lives of railroad workers), taking a leadership role in the organization and as editor of their magazine, The Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine. At Debs’s urging, Harper became an editor of their “Woman’s Department” section of the magazine for nearly ten years. [i] [ii]

Harper also began writing for the Terre Haute Saturday Evening Mailin the early 1870s. Her early columns focused on various topics, from art to religion to social norms. Throughout her career, her columns eschewed conservatism and refinement, both in advocacy roles and in domestic spheres. For instance, one 1911 interview with Harper, published in the Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegraph, decries the influence of immodest clothing as extremely detrimental to the cause of suffrage, stating, “nothing has done so much harm to suffrage in the last fifty years as the way women have dressed themselves in the last year or two.”[iii] This progressive duality was also displayed in another article in 1882, stating both that “nothing is impossible to a sensible, energetic, determined woman” but that “women have no love stronger than that of home, no ambition greater than to be a perfect housekeeper.” [iv]

However, she often wrote on cultural elevation for women, encouraging education and endeavors beyond the home.[v] An article in 1878 focused on the importance of women seeking to better themselves, either with or without the support of their husbands:

Reading, writing and good society have a refining and elevating influence upon a woman. They lift her up from the household drudge, and make her the equal and companion of her husband (and frequently his superior). A woman who never reads, writes, or goes out into company must expect to detoriate. One who writes has, perhaps, the hardest time. She must expect to do like Harriet Beecher Stowe, who, ‘it is said, wrote the best pages of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, “while watching the pot boil for dinner and trying to amuse the little children clinging to her skirts.” [vi]

“A Woman’s Opinions” was published for nearly twenty years during Harper’s time in Terre Haute. Harper briefly became the editor of the Terre Haute Daily News early in 1890, following her divorce from Thomas, but left the city and job within months of starting.[vii] Moving to Indianapolis, she began writing for the Indianapolis News, which she continued throughout the next few decades as a correspondence journalist.

However, it was the connection to Debs that led Harper to one of the most productive relationships in her career and her development in the Suffrage Movement. In 1878, Debs brought Susan B. Anthony to Terre Haute for a speaking engagement, which was the first occasion Anthony and Harper met. The two continued their professional relationship in the Suffrage Movement, but also became personal friends. It was Harper who wrote both volumes of Susan B. Anthony’s biography, and the two would co-write portions of the History of Woman Suffrage, (though the final two volumes would not be completed by Harper until after Anthony’s death and the passage of the 19th Amendment).

Harper became increasingly involved in statewide efforts towards suffrage, eventually becoming a leader in the National American Woman Suffrage Association and an International Council of Women representative at both the London and Berlin conferences. She also frequently appeared as a guest writer for papers throughout the country due to her prominence in the Suffrage Movement. Columns written by Harper appeared primarily in the areas in which she lived, including newspapers in Indiana, California, New York, and Washington, D.C., as well as magazines like Harper’s Bazaar. She remained active in the field of women’s rights as an advocate, even after the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1919.

Mary Hannah Krout

While Ida Husted Harper became primarily known for her work throughout the nation, Mary Hannah Krout was best known for her travels outside of the continental United States. A contemporary of Harper, Krout was born and raised in Crawfordsville, Indiana. Krout was mentioned in a previous Hoosier State Chronicles blog post, but her influence in the newspaper and publishing world extended beyond her contributions in Indiana. Beginning in her teen years, Krout was an avid poet and writer. “Little Brown Hands” received wide circulation throughout the community and the United States, as did many of her other poems of lesser fame.[viii] Not only did she excel in poetry early on, but she also became known as a public speaker in the Crawfordsville area by her mid-teens. Additionally, her sister Caroline Virginia Krout followed her lead, writing for local papers as “Caroline Brown” and writing four books.

Krout also had the support of a benefactor and family friend: Susan Wallace, herself a writer and wife of Lew Wallace, famed author of Ben-Hur. In one article from the Cincinnati Gazette about Lew Wallace, Krout made sure to highlight the efforts of Susan:

General Wallace has been peculiarly fortunate in his marriage. His wife is a woman of rare mind and character. There is no doubt but that much of his success is due to her faith in his genius and to her intelligent sympathy; she has been a careful and discriminating critic, aiding him continually in his literary work.[ix]

Wallace’s and Krout’s friendship and collaboration continued throughout the years, and it was Krout that assisted Susan Wallace in completing and editing Lew Wallace’s autobiography after his death in 1906.

Krout’s newspaper work began with a column at the Crawfordsville Journal and periodical writing at the Indianapolis Herald, both under pen names.[x] She shifted to writing under her own name by the 1880s, taking positions as associate editor at the Crawfordsville Journal in 1883, as well as writing and editing the “After Breakfast Chat” column for the Terre Haute Weekly Gazette. Eventually, Krout moved to Chicago and took a position at the Chicago Inter-Ocean in 1887. It was during her time writing the “Woman’s Kingdom” column that Krout gained publicity for her international travels and perspectives on social issues affecting women. Krout’s travels to the Hawaiian Islands resulted in several books, not only about the territory, but about the end of the monarchy of Queen Liliʻuokalani, (whose rule Krout originally supported, before eventually shifting her opinion to American rule).

She also traveled to London, where she often discussed the social role of women in England for the Inter-Ocean. This article below argues for the equivalent of Knighthood for women in service to the Queen:

Her time abroad helped to inspire seven books relating to her travels, including A Looker On in London and Two Girls in China. While she continued writing columns for newspapers, her career shifted to speaking engagements about her travels and views on women’s rights. One speech in Chicago, published in the Crawfordsville Daily Journal in 1897, discussed her views on women’s voting:

Two years ago a woman living in one of the suburbs drove up to the polls and held the horses while her coachman, who could not read or write, went in and voted, and she was paying taxes on $1,000,000 worth of property… The husband who represents the woman must represent her always before the law. When he votes for her, if she violates the law… he should be made to represent her as he did at the polls, unless the men of this country will admit that they don’t represent women in everything. I think in time they will say: “God-speed to equal suffrage; let the woman vote for herself.” [xi]

Her chastisements were not only directed towards men, but also women who overly criticized other women in the cause:

It becomes necessary on occasion for a woman to speak sharply, sternly, unflatteringly; but this can be done only by those who desire for their sister women the highest excellence they are capable of achieving, and the greatest good they are capable of attaining- a right of censorship that they have humbly endeavored to earn by disinterested affection, and by constant and unquestionable sympathy. [xii]

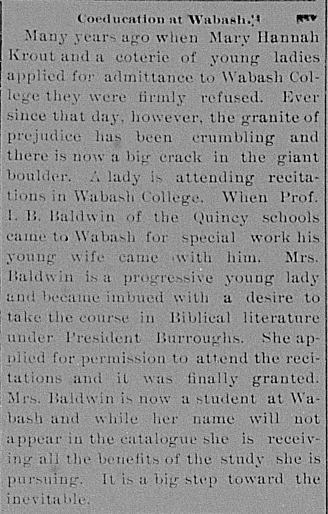

Equity in education was also important to Krout. Like Harper, she too served as a school teacher for several years, and even unsuccessfully applied as a student to Wabash College. One article from 1894 even credited the early effort into the “admittance” of a woman to attend classes at Wabash that year, (despite her efforts and what the article dubbed “the inevitable,” Wabash College still only admits men today):

While Krout was apparently not involved in national suffrage organizations, she was involved in Chicago press associations throughout her time in the city, including a Women’s Press Association. Her international reporting into the challenges faced by women in London, her public speeches throughout the United States, and bold reporting in newspapers in Crawfordsville, Indianapolis, and Chicago provided an active female voice in the news.

Esther Griffin White

While the western half of the state was influenced by the writings of Krout and Harper throughout the late 19th century, the early part of the 20th saw a rise of women’s political discourse in Richmond due to the work of art columnist Esther Griffin White. White wrote for the Richmond Palladium, and also pursued her own interests through an infrequent, self-published newspaper, referred to as The Little Paper.[xiii] In the 1910s and 20s, White sought political offices within Indiana.

Born to a Quaker family from Richmond, White was influenced at an early age by Mary F. Thomas, the first woman admitted to the Wayne County Medical Association and an early suffragist, and Louise Vickroy Boyd, an author, poet, and advocate for women’s rights.[xiv] Alongside these role models stood her family, an eccentric mix of educators and journalists, who likely influenced White’s own non-conformity. George Blakey details her public persona in his profile of White for the Indiana Magazine of History:

As early as 1915 she smoked publicly and criticized those who disapproved. Her fashion sense was either a step ahead or behind contemporary styles; her skirts were either shorter or longer and her hats larger or smaller than those worn by other women of the time. She often affected a masculine look, abetted by a cane carried in the manner of a swagger stick… Her opinions were firm, her wit caustic, her temper volatile; she demanded cooperation, favors, and applause, yet her self-conscious detachment made her appear aloof and unfriendly. Many people found her temperament endearing or considered it a reflection of her high standards and ambition. Others, less charitable, regarded her as rude, profane, and condescending. [xv]

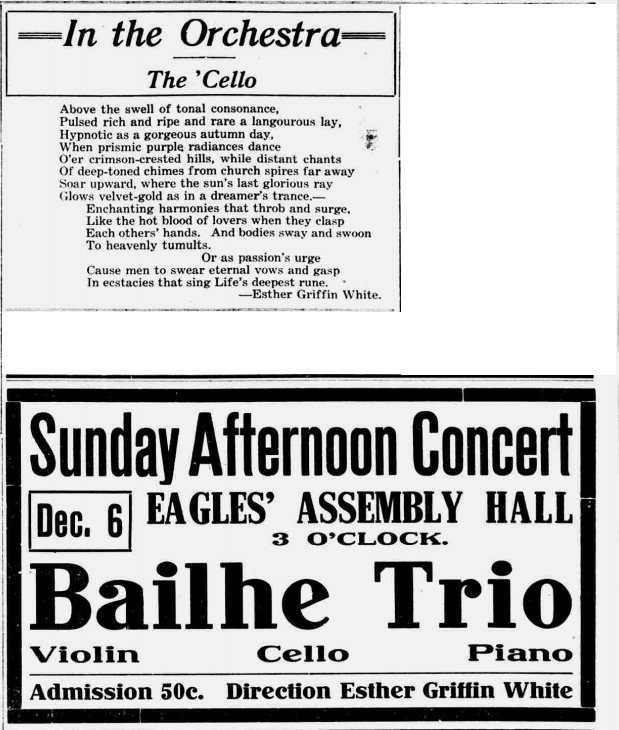

Yet, this bold, (and slightly antagonistic), style carried over to her impressive writing career. In the late 1880s, White began her career with little formal secondary education, but gained experience through self-determined freelance jobs for multiple newspapers in Richmond, (a trend, Blakey contends, that continued for most of her career due to her adversarial writing style). Despite her reputation for dogged and direct journalism, her time at the Richmond Palladiumbegan as a critic of arts and culture. An active member of the city’s arts community, White was as comfortable directing an orchestra as she was composing a poem:

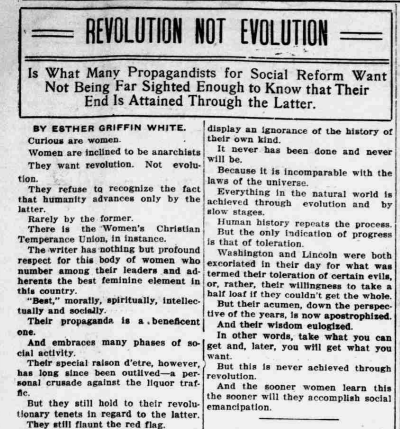

Her ability to passionately advocate for issues, particularly of women’s suffrage and African-American rights, are also prevalent in her articles, even when critical to approaches in the movements:

“Revolution Not Evolution” urged an understanding of gaining and earning credibility for social reform through smaller gains and changes, rather than a dramatic and sudden shift in culture. Underlying this, however, is her critique of the Women’s Temperance Union, whose “personal crusade against the liquor traffic” missed the mark by trying to do too much all at once, rather than making manageable changes to society.

In “Are They Sincere?,” White strongly advocates for the franchise of women in their roles as leaders and workers, but critiques anti-suffrage proponents as lacking motivation and merit.

By the end of the 1910s, White’s desire to affect change in the lives of women focused on action, rather than writing. Joining the Women’s Franchise League, a local competitor of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, White became a fervent advocate of the movement in various campaigns throughout the state. However, her desire to seek greater political and social representation of women led her to run for a delegate seat at the 1920 Republican Convention. Despite strong opposition and no publicity in either the papers or political correspondence, a judge allowed White to appear on the ballot for the convention, making her the first woman to appear on a political ballot in Indiana history. She was eventually elected a delegate for the convention, receiving the second most votes in Richmond. Unfortunately, despite several campaigns for the position of Mayor of Richmond and a run for a 1926 seat in the US House of Representatives, White was never elected to office. By the 1930s, with her career in both newspapers and politics waning, Griffin’s social presence greatly relied on her connection to the Hoosier artists she befriended and lauded throughout the years rather than her contributions to social rights and political activism. Her collection of art and writings were left to Earlham College in Richmond, which recently featured an exhibit on her life and career.

Conclusion

Each of the women engaged in varying degrees of activism, and each reached a level of success within the field that was rare for the time. They were also dramatically different in how they approached the question of social equity and equality. For instance, White’s brash, politically-charged style certainly did not mesh with Ida Husted Harper’s conservative and restrained leadership, but both were heavily involved with local and international organizations. Mary Hannah Krout travelled the world and brought perspectives of women in London to the people of America, unlike the localized reporting of White, but Krout’s advocacy was much less formal. Though all three were involved in newspaper reporting at roughly the same time, Hoosier State Chronicles staff was unable to find evidence of these women crossing paths.[xvi]

However, their stories share more similarities than differences. All three women sought higher education at a time where women were limited in access. All three started off writing under assumed names to get their start in a male-dominated sphere of newspapers, and all three ended up writing for prominent organizations through their abilities and unique voices. Each had ambitions beyond their craft of journalism, and gave back to their communities through books, arts, and poetry. Most importantly, all three women gained the right to vote within their lifetimes.

The power of local newspapers gives voice to a community that may be minimized in national papers allow individuals to share lived experiences and opinions in a semi-permanent format. Through Hoosier State Chronicles, the public has widespread access to these stories and we are now able to connect the local stories to the larger narrative of suffrage in America. In this, we are highlighting the local individuals who fought for early 20th century women’s rights, extending far beyond the voting booth into political offices, employment, and acceptance in male-dominated spaces. More than that, digital newspapers allow us to better represent contemporary histories from communities throughout the state and country, bringing a better understanding of our shared past.

With the centennial of the 19th Amendment approaching, projects like the Indiana Women’s Suffrage Centennial and the 2020 Hoosier Women at Work History Conference seek to bring these stories to the forefront. We encourage researchers to utilize Hoosier State Chronicles to uncover other Indiana women who helped shape the movement, and present their findings through these projects.

[i] Harper also published for the magazine under the name “John Smith”, according to the Jan 18, 2015 edition of “Historical Perspectives” in the Terre Haute Tribune Star: https://www.tribstar.com/features/history/historical-perspective-ida-harper-and-lenore-cox-among-local-suffrage/article_11864449-5a7f-584a-b8cf-602739e999b4.html

[ii] Leigh Darbee’s brief biography of Harper in Indiana 200 suggests Thomas Harper opposed his wife’s writing on the basis of being paid, which was considered inappropriate for a married woman at the time.

[iii] “Immodest and Freakish Clothes are Deplored by Women as Bar to Suffrage”, Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram, November 22, 1911, p. 4. Hoosier State Chronicles

[iv] “A Woman’s Opinions: Cooking” from the Saturday Evening Mail, November 11th, 1882, p. 1. Hoosier State Chronicles

[v] Harper was a strong advocate for the education of women. She attended private schools as a child, briefly attended Indiana University in Bloomington before becoming a teacher and principal, and supported her daughter’s education with May Wright Sewell at the Girl’s Classical School in Indianapolis and at Stanford University in California.

[vi] “A Woman’s Opinions” from The Saturday Evening Mail, November 9th, 1878, p. 1. Hoosier State Chronicles

[vii] See endnote ii. The cause of the divorce is unknown, but her status as an advocate and public figure over the objections of her husband, a lawyer in the community, may have contributed to the end of their marriage.

[viii] An article from the Honolulu Times on February 1, 1911, (found on the Library of Congress Chronicling America website), discusses the process of writing the “Little Brown Hands”, as well as a complete copy of the poem: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85047211/1911-02-01/ed-1/seq-9.pdf

[ix] “The Author of Ben-Hur”, Date Unknown. Originally published in The Cincinnati Gazette, clipping part of the “Mary Hanna(h) Krout” collection at the Indiana State Library (L80)

[x] Author Kenneth Turchi noted in a 2013 speech to the Indianapolis Literary Club that Krout’s wrote under the names “Ben Offield” for the Herald and “Mynheer Heinrich Karl” for the Journal, backed up by the prodigious scrapbook of articles by these authors in her personal papers at the Indiana State Library. The collection of newspaper clippings alongside articles under these pen names may suggest she may have written under other pseudonyms not currently credited to her.

[xi]Crawfordsville Daily Journal, November 20, 1894. Hoosier State Chronicles

[xii]The Inter-Ocean, June 28th, 1897, from Newspapers.com (Subscription required)

[xiii] Quite a few of the editions of The Little Paper still exist within personal papers of White within the special collections of Earlham University.

[xiv] For more information on Mary F. Thomas early role in women’s suffrage, read “A Public “Jollification”: The 1859 Women’s Rights Petition before the Indiana Legislature” from The Indiana Magazine of History, Volume 72, Issue 4, December 1976. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/9961

[xv] Blakey, George. “Esther Griffin White: An Awakener of Hoosier Potential,” Indiana Magazine of History, Vol. 86, No. 3 (September 1990), pp. 284, 286. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/11072

[xvi] There may be evidence of some of the women attending Chautauquas in Richmond, which were educational and social events designed to feature intellectual ideas and figures.