Southern Indiana has been home to some pretty remarkable women. Their impact still ripples through the streets of New Albany, along the Ohio River in Jeffersonville and beyond any downtown. Many readers will recognize at least one of these names, or perhaps more likely, the names of the men in their life. But their own stories beg to be shared.

This Women’s History Month, the News and Tribune chose just a handful of such stories. By chance, the tales of Blanche Culbertson, Loretta Howard, Clementine “Tiny” Barthold and Lucy Higgs Nichols were relayed mostly through other women; women who have devoted themselves to bringing their stories into the light.

Step out of the shadows with us to meet the first two of our four historic Southern Indiana women, and pick up Monday’s paper for part two.

THE SUFFRAGETTE FROM NEW ALBANY

After raising three children, Blanche Culbertson found herself smack in the middle of the women’s suffrage movement in New York City. She had been raised, of course, in New Albany. Born to William and Cornelia Culbertson in the fall of 1870, she was the only one of the 10 Culbertson children to be born in the nearly 21,000 square-foot mansion on East Main Street.

Jessica Stavros, southeast regional director for Indiana State Museum & Historic Sites, called Blanche “the baby of the richest family in the state,” and admitted she was probably a little spoiled. But she was also influenced by a spirit of activism that possessed her family.

William and his third wife, Rebecca (Cornelia, his second wife, died when Blanche was 10), were heavily involved in the women’s suffrage movement in New Albany. So much so that when Susan B. Anthony and her successors were in New Albany for a suffrage meeting, “they would have absolutely been working hand in hand with the Culbertsons,” Stavros said. Blanche grew up around the movement, and saw through the widow’s home her father opened just how far behind women were left. Coupled with her Presbyterian upbringing that promoted service, it’s no surprise Blanche would go on to do great things.

But first, a detour. After her father died in 1892, Blanche eloped with Leigh Hill French, a man considered “unsuitable” for his reputation with women. So unsuitable that before William Culbertson died, he revised his will to cut Blanche out of her inheritance should she marry Leigh. What followed was a successful, but very public legal battle to contest the will.

Blanche and Leigh eventually had three sons, lived in Europe for some time, and later settled in New York. After her sons were raised, and while Leigh was off pursuing other ventures, Blanche became involved with the suffrage movement.

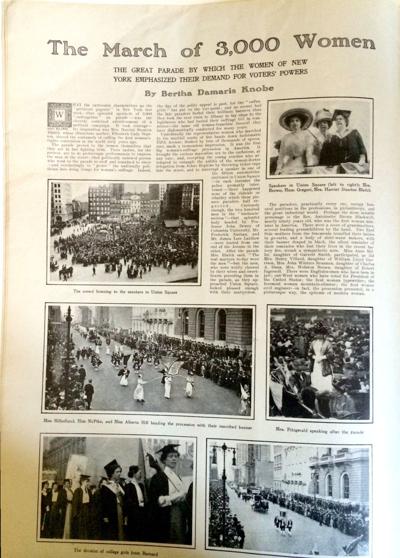

You’ve probably seen the iconic photos: a parade of suffragettes marches along Fifth Avenue in New York City, waving banners that demand the vote. In one of those photos, Stavros said, Blanche is seen being carried through the streets on a sedan chair. She was called “The Little Lady of the Olden Days.”

“Because she was one of the women from the beginning of the suffrage movement hanging out with Susan B. Anthony in New Albany, Indiana, in 1880,” Stavros said. “So she was considered a midwestern movement, that now had a lot of money and incredible influence in New York City.”

In 1917, women claimed their right to vote in Westchester County, New York. Three years later, the 19th Amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified, granting American women everywhere the right to vote.

Blanche lived in New York until her death in 1924, but returned to New Albany for family visits. Wherever she was, Stavros said, Blanche never let people forget where she learned her suffragette ideals: “From the women in my home in Indiana.”

THE MAID WHO BECAME A MOGUL

Fifteen years before Blanche was born, another woman who would grace an iconic Southern Indiana mansion entered the world: Loretta Maude Wooden.

At 21 years old, Loretta was hired to work as a house maid for Edmonds and Laura Howard in their towering, Victorian mansion on East Market Street in Jeffersonville. The family was in the steamboat business and their home sat just across the street from their shipyard that would one day become JeffBoat.

Soon after arriving at the mansion, Loretta discovered she had much in common with Jim, one of Edmonds and Laura’s two sons. Kadie Engstrom, education coordinator for the Belle of Louisville and a docent at the Howard Steamboat Museum, said that while some people might have guffawed at the idea of wealthy Jim Howard marrying a “housekeeper who had no means of her own,” the two married without much fuss.

“She became the business woman of the Howard shipyard,” Engstrom said. “Jim was a mechanical genius, not so good on business. She couldn’t have done anything on mechanics, but she was an amazing businesswoman.”

Image from http://digital.library.louisville.edu/cdm/ref/collection/howard/id/1627

After Edmonds Howard died in 1921, Jim and his brother, Clyde, took over the shipyard business. Then in 1923, when Clyde sold his share, Loretta stepped up in a big way.

Together, Jim and Loretta — who was now the company’s vice president and business manager — ran the shipyard for 17 successful years.

“For her era, she was an amazingly skilled woman; skilled in business and skilled in people,” Engstrom said. “So in her own way, she was a major part of what happened here and a major part that connected to river history.”

Before Jim died in 1956, he tasked Loretta with turning their mansion into a museum. Two years later, she realized that vision, becoming the Howard Steamboat Museum’s first tour guide. She lived on the third floor of the mansion until 1969 and stayed involved with the museum for the rest of her life.

In 1978, at 93 years old, Loretta died, leaving behind a history preserved for the ages and a reputation as the “steel magnolia” of the Howard family.

Image from http://digital.library.louisville.edu/cdm/ref/collection/howard/id/1628

Reposted by permission of newsandtribune.com. This post was first written by Elizabeth Depompei on 23 March 2019.